|

Aircraft Wrecks in the Mountains and Deserts of the American West This Article Appeared in the Antelope

Valley Press, August 21, 2005 'Wreck hunters' examine B-24 bomber crash siteBy ALLISON

GATLIN

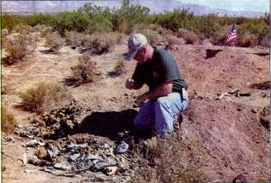

MOJAVE - On April 9, 1944, an Army Air Corps B-24 bomber on a training mission from March Field crashed in the desert near Mojave, killing all 10 crew members on board. More than 60 years later, relics from the crash have been unearthed in an attempt to reunite some effects with family members of the crew. The crash site west of Mojave was located about a year ago by amateur aviation archeologist Don Jordan, following years of combing the desert for the rumored spot. Jordan is one of a closely connected group of "wreck-hunters," hobbyists who spend their weekends and free time locating and documenting the numerous airplane crash sites scattered across the state. Typically, these history buffs are in it strictly to locate evidence of the wreckage. They try not to disturb the sites out of respect for the dead and the historical significance of each accident. "It's the thrill of the chase," said Walter Witherspoon, who began locating and researching crash sites 10 years ago when stationed at Edwards Air Force Base. This particular site became unique, however, when the niece of the bomber's radio operator contacted Jordan about his find, wanting to obtain artifacts from the wreckage for her family's own use. Sgt. Michael Rudich's surviving family members in South Carolina hoped to receive personal effects or parts from the bomber's radio console, where he worked. At the time of his death, Rudich's family received a coffin for burial, with what was reported to be his remains inside. However, from the damage inflicted by the spectacular crash, it is unclear if any of the 10 on board were correctly identified. In searching the site for dog tags or other personal effects, wreck-hunter David Schurhammer unearthed bone fragments as well. Because what appeared to be human remains were found, coroner's investigators were brought in to handle the official processing. On Saturday, Kern County Coroner Investigator Kelly Cowan took control of the bone fragments, laying them out on an Army blanket to examine what was there. She was assisted by David Van Norman, supervising deputy coroner for San Bernardino County. Although Van Norman does not have any jurisdiction over the site, he has participated in several such finds in the past and has a personal interest in investigating old airplane crashes, he said. Cowan and Van Norman examined the bone fragments, few larger than a couple inches. "Looking at this, you get an idea of the force of the impact," Jordan said. Deciding there was enough evidence to support further investigation of the site for additional remains, Cowan and Van Norman recorded the precise location, and they began excavating the main crater further. Kern County will take possession of the remains, then inform the Army of the find. If the Army has no interest in identifying the remains, the county will proceed with its own forensic investigation, Cowan said. The wreck-hunters typically begin their searches with some kind of contemporary account of the accident, usually a newspaper report. "From there it's just doing book work and research," Witherspoon said. Many hours are spent retrieving and poring over military accident reports, local newspapers and other archival materials. According to witness' reports from 1944, the bomber in this case was seen coming out of a thundercloud, apparently out of control, and hit the desert floor at a high rate of speed. Evidence of the force of the crash is still apparent. A main crater where the fuselage plowed into the earth is flanked by four smaller craters extending out on either side where the bomber's four wing-mounted engines hit. Evidence from the engines has been found in the smaller craters. The debris field covers about four acres, aviation archeologist Pat Macha said. Scattered about the desert scrub are remnants of the destroyed aircraft: pieces of plexiglass from the windows, a hydraulic valve, bolts and metal plates. Among the artifacts unearthed when Schurhammer began digging in the main crater are many small, melted pieces of metal, buckles from parachute harnesses and even pieces of uniform zippers. Personal effects - the navigator's dog tag, coins, a couple rings - were carefully labeled and bagged. "Our attitude is that sites are to be conserved, not disturbed," Macha said. However, if personal effects are discovered, every effort is made to return them to the flyer's next of kin. "Ninety-eight percent of the time, people are happy to receive these things," he said. The Mojave Desert is ripe for aviation archeology, as the area was a popular site for flyers during World War II. According to Macha, some 35,000 airmen and airwomen were killed in the United States during World War II, either on training missions or ferry flights. Jordan spent three years looking for this bomber crash site, a search hampered because initial reports of its location were misleading. Working where he believed it may have gone down, Jordan created a grid using a Global Positioning Satellite system and systematically combed the area. "I covered every damned inch," he said. Eventually, he came across an oil-pressure gauge, "then I knew I was getting close." He found some parts with serial numbers that indicated they were from a B-24, although not which airplane specifically. "Then, when the dog tag was found, that pretty much told us that navigator was on this plane," Jordan said. |

|

|