|

Aircraft Wrecks in the Mountains and Deserts of the American West This Article Appeared in the San Diego

Union-Tribune, January 22, 2006

Son

finally says farewell By Greg Moran January 22, 2006 Down the side of Otay Mountain, in a plunging crease carved out of the rugged terrain, Marc Harding said a kind of farewell to his father yesterday.

It came almost 45 years after Lt. Henry M. "Hank" Harding died while on a routine mission in his Navy FJ-4 Fury. Over the decades since his father's death March 27, 1961, Marc Harding believed there was no wreckage of the plane ever found. But last year, while searching on the Internet for people who may have flown with his father, he was put in touch with Pat Macha and his son Patric, who have located wreckage of scores of military planes across California. In 1998, Macha and his son had found the wreckage of the Harding plane. Macha, a Huntington Beach resident, told Marc Harding and volunteered to take him to the site. "Finding out over the summer that there was wreckage was shocking," Harding said during a pause on the taxing hike down the mountain yesterday. He debated whether to go and visit. "I didn't know if I wanted to come down, because it's not a real happy place to me," he said. Harding, 48, a computer engineer, has only a few memories of his father. A trip to an amusement park. Lying on the couch of their Chula Vista home with his dad, watching a baseball game. Peering out the window, waiting for him to come home at night. "Eventually, I decided I couldn't go through the rest of my life, knowing the wreckage was there, and not ever going there to pay my respects," he said. He contacted Macha, and in October he flew from his home in Portland, Ore., to visit the site.

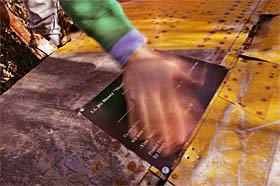

But thick fog that day swaddled the mountainside and made finding the site in the heavy brush impossible. He had to turn back. It was an eerie coincidence, because thick fog played a major role in the crash of his father's plane in 1961. The senior Harding, then 27, was flying to Brown Field, where his squadron was based, from Yuma. He was following a flight path, or vector, given him by the control tower at North Island Naval Air Station. There was some confusion at the tower, however, and – swallowed up by the bad weather – the plane slammed into the side of the mountain. The crash site was spread out over some distance. The plane appeared to have hit a ridge, then skipped over before breaking up, Macha said. The weather yesterday was perfect – clear and cool. To reach the crash site the group drove up a twisting, rutted unpaved road that snaked up the side of the mountain. They parked in a small turnout below the summit. Armed with a topography map, Global Positioning System and working off their memories from 1998, Macha and his son led the way off the side of the peak. They worked their way down the steep side amid heavy brush. After about a half-hour, pieces of the wrecked plan appeared amid the scrub. A shard of plexiglass from the canopy. A chunk of fuselage about the side of a wallet. Other pieces were much bigger. At one spot, a section of the wing about 6 feet long lay on the ground. Harding knelt beside it, alone, for several minutes. Chunks of the plane were remarkably well preserved with the original paint, still bright, stenciled writing, clearly visible. Eventually, the group found another large chunk of airplane wing. As they huddled around it, Harding took out of his backpack a small plaque. It had his father's name and rank, his birthday and date of death. "To our loving son, brother, husband, father," it read. "We miss you so much. We will forever love you. We will never forget you." He held it in place carefully while Dave Schurhammer, who also works with the Macha family on wreck sites, screwed it into place. Later, after the long hike out, Harding reflected on the day's events. He had said that placing the plaque did not necessarily close a circle for him, but after coming down from the mountain he said the effort was worth it. "When my Dad died, he was doing something honorable," he said. "And I wanted to honor that."

© Copyright 2006 Union-Tribune Publishing Co. • A Copley Newspaper Site |

||

|

|

||