|

This Article Appeared in the Star-Ledger,

May 31, 2004

Link to the Star-Ledger

Still missing

But

this flygirl has not been forgotten

Monday, May 31, 2004

BY JUDY PEET

Star-Ledger Staff

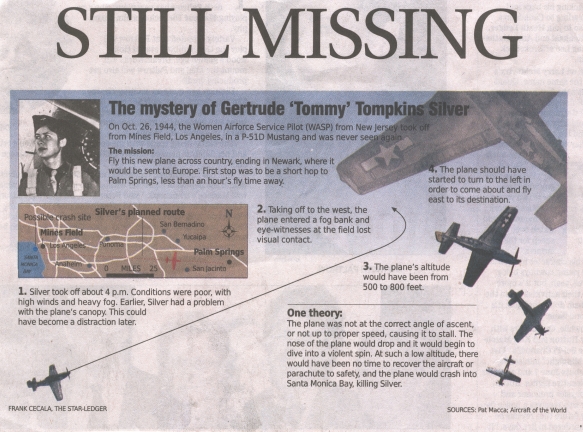

Late in the

afternoon of Oct. 26, 1944, a small, extraordinary, 32-year-old newlywed from

Jersey City climbed into the cockpit of a brand new P-51D Mustang at Mines Field

in southern California, wrestled the hulking fighter plane into take-off in

heavy fog and disappeared.

She was

Gertrude Tompkins Silver, the other Amelia Earhart; one of 1,074 women Air Force

pilots in World War II and the only one still missing.

For decades,

what ever happened to Silver has been a tantalizing mystery.

Did she stall

and spin right after take-off? Crash into the San Bernardino Mountains?

Commit suicide or just head off into the horizon in search of a new life.

Sixty years

later, the mystery finally may be solved, if enough money can be raised to

investigate the wreckage.

Silvers

remaining family, working with a small, dedicated band of aviation archeologists

(plane wreck buffs) think they have found the remains of her aircraft buried

under 15 feet of silt in Santa Monica Bay, not far from the back end of Los

Angeles International Airport (the former Mines Field). The family has no

intention of raising the lost plane. They just want closure, said her

grand-niece, Laura Whittall-Scherfee of Sacramento, Calif.

They want a

place to scatter some flowers and say a few words of good-bye to the stuttering

girl with beautiful hair from Kent Place School who traveled the world visiting

gardens and goats, before she found her real passion, flying,

Our goal is

just to try to find out what happened to my great-aunt before my grandmother

dies, said Whittall-Scherfee, referring to Silvers older sister, Elizabeth. It's

not like we sit around all the time wondering what happened to Gertrude, but

it's frustrating that it's been in limbo for so long.

Elizabeth

Whittall, 95, another extraordinary woman, actually doesnít care that much if

the identified wreck turns out to be her sister.

I made my

peace with Gertrudeís disappearance long, long ago, and think any money spent

trying to get to her plane would be better spent on poor people or feeding

children, said Whittall, who after living in far-flung parts of the world for

most of her life, settled in Vero Beach, Fla.

But my

grandchildren have gotten so wrapped up in the excitement of finding Gertrude, I

donít want to disappoint them, Whittall added. They have made it an adventure

and I definitely approve of adventure.

Adventure,

Whittall said, was held in high esteem by the Tompkins family.

They were

among the early settlers of Jersey City,

although upper middle-class comforts didnít arrive until Gertrude and

Elizabethís father, Freeland Tompkins opened the Smooth-On iron cement factory

in 1895.

Iron cement

was used to repair water and steam leaks in cast iron products, such as boilers.

Smooth-On was an instant success in those expansionist times and Silver was able

to send his three daughters, Margaret, Elizabeth and Gertrude, to private

schools.

Their mother

had wanted to be a missionary in China, Elizabeth said, but was in too poor

health, so she passed her dreams onto her children.

Margaret, the

eldest, followed a more traditional path, going to Vassar and marrying a banker.

Elizabeth took the leap, however, moving to Damascus after graduating Wellesley

in the 1930s to teach at a Muslim school. She later lived in South Africa,

Madagascar and Egypt.

Gertrude, the

baby, had a rough start. She was shy, somewhat withdrawn, and plagued by a heavy

stutter. She did poorly at Kent Place,

and was sent to the country for a year, where she didnít loose her stutter but

did gain a strong fascination for goats.

She graduated

from college with a degree in horticulture and returned to Summit, where her

family had moved, and raised goats. She visited the great gardens of the world,

traveling alone. She tried to convince the Australian government to invest in

goats, not cows, because they were ecologically and nutritionally superior.

Then she met

a young pilot, who taught her to fly. That was it Whittall said. She loved it.

She didnít stutter when she was in a plane, or the whole time she was in the

WASP.

WASP, Womens

Air force Service Pilots, was an experimental program that hired licensed women

pilots to fly all military aircraft stateside, freeing up male pilots for

combat. After Silvers flyer beau and fiancťe (whom her family will not identify)

was killed in combat, Gertrude was among the 25,000 women who applied to the

WASP, and among the 1,074 who were accepted and passed basic training.

Some of the

women were too small to handle the big fighter planes. Although slender, Silver,

at 5-foot-5, became certified on every type of military plane. She also got

married -- to Henry M. Silver, an accountant -- in September 1944, although her

superior officers didnít find out until she disappeared.

Some friends

and family say she married on the rebound and regretted the decision. Others say

she may have been despondent, possibly suicidal.

Whittall and

her granddaughter say that is hogwash.

Gertrude

wouldnít have killed herself, and even if she did, she was too proud of being a

WASP to take the plane with her, Whittall said. And we joked that she might have

taken off, but she was too close to her family to ever do that without telling

us. I donít know what happened, but it wasnít that.

What they do

know is that three planes fresh from the factory were to leave Mines Airfield on

the morning of Oct. 26 and head east for delivery to the European front.

The flight

was delayed because of mechanical difficulties with Silvers plane. Among the

problems was a malfunctioning canopy, which would have made it impossible for

her to eject.

By the time

the three planes left in the late afternoon, conditions had deteriorated. Fog

had moved in and a nasty wind had whipped up. The pilots took off anyway,

circled around and headed for Palm Springs,

the first leg of their journey, said Pat Macha, a widely recognized aviation

buff who has helped find more than 1,000 downed planes.

Macha has

been helping the family search for Silver remains since he met her grand-nieces

husband at an air show more than a decade ago. Fascinated by the story, he

agreed to pick up were Whittall-Scherfees father left off on in his search in

the 1970s.

I looked at

the clips and the reports and talked to a guy who flew with her. She was good

and she was gung ho. There where no crybabies or ninnies in the WASP, said

Macha, a retired high school history teacher who helps families locate missing

planes.

At first we

thought she had made it to the mountains, and checked there, but all the wrecks

were accounted for, Macha said. But I knew that the day she took off, three

planes took off, but only two were seen circling back over the field.

Macha's

theory is that Silver crashed almost immediately after take-off. The fighter

plane was heavy, he said, and had a nasty tendency to stall and spin, which

means that if airspeed wasnít achieved, the plane would go into an immediate

dive, giving Silver no chance to eject, or even react.

Using

expensive equipment that detects metal and mass on the ocean floor, Macha has

found lots of planes. But not the right one. Part of the problem is that the

plane probably would have broken up on impact and doesnít look like a plane any

more.

Another

problem is that the area was used to deposit silt when the harbor was dredged

several years ago, which means the wreckage is buried under a small mountain of

sand.

Now, Macha

thinks he has found the right mound of metal, but we can't be sure until we get

in there and find out if itís a P-51D, he said.

If it is, it

is almost undoubtedly Silvers plane, since hers was the only Mustang lost in

that region during the war. To find out will cost between $15,000 and $25,000,

that we really donít have right now, said Whittall-Scherfee.

So we wait,

and try to raise more money and maybe get more tests that will better our odds,

Whittall-Scherfee said. Were looking for a sponsor, but people arenít all that

interested in a women pilot who disappeared 60 years ago.

But we wonít

forget. Well never forget Gertrude.

|